If you have ever seen the phrase AES-256 on a security page and wondered what it actually means, this guide is for you. In plain language, we will explain what AES-256 encryption does, why it is considered trustworthy, and where it fits in a practical security workflow for sharing sensitive information.

What AES-256 is, in plain English

AES is a recipe for scrambling data so only someone with the right key can read it. The letters stand for Advanced Encryption Standard, a public standard selected and published by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. The "256" refers to the size of the secret key, 256 bits, which determines how hard it is to guess the key by brute force.

Think of AES as a very secure lock, and the 256-bit key as a key with a mind-boggling number of possible shapes. If you have the key, opening the lock is easy and fast. Without it, trying every possible key is so impractical that it is effectively impossible with today's computing power.

If you want the original definition, AES is standardized in NIST FIPS 197, which means its design has been public, vetted, and tested for years.

Why so many organizations trust AES-256

- It is openly specified and has been reviewed by cryptographers for over two decades.

- It is fast and widely supported, including hardware acceleration on modern CPUs, for example with Intel AES-NI.

- NIST guidance treats 256-bit keys as offering very long term protection, see NIST SP 800-57 Part 1.

The takeaway for non-engineers: AES-256 is not a boutique algorithm. It is the workhorse standard used virtually everywhere sensitive data must stay private.

What "256-bit security" really means

A 256-bit key has 2^256 possible values, an astronomically large number. Even with massive computing resources, systematically guessing the correct key would take far longer than the age of the universe. That is why you often hear that brute-forcing AES-256 is infeasible.

However, encryption is only as strong as the rest of the setup. Weak passwords, unsafe key handling, or implementation bugs can undermine even the strongest cipher. Keep that in mind as you read on.

AES is the lock, the "mode" is how you use it

AES is a building block. To encrypt more than a tiny chunk of data safely, systems use modes of operation. Modes determine how data blocks are processed and whether the system also checks for tampering.

- Some modes only hide the content (confidentiality). Examples include CBC and CTR, documented in NIST SP 800-38A.

- Modern best practice uses authenticated encryption, which hides the content and detects changes in it. AES-GCM is a well known example, defined in NIST SP 800-38D.

For non-engineers, the difference is simple. Confidentiality prevents eavesdropping. Authentication prevents silent tampering. In most real world applications you want both.

AES-128 vs AES-192 vs AES-256 at a glance

| Variant | Key length | AES rounds | Typical use notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES-128 | 128 bits | 10 | Very widely deployed, strong for many use cases |

| AES-192 | 192 bits | 12 | Less common in practice |

| AES-256 | 256 bits | 14 | Chosen for long term confidentiality and high assurance scenarios |

All three use the same 128-bit block size. In many systems the performance difference is minor because of hardware support. The choice often depends on policy and desired security margin over time.

Where you encounter AES-256 in everyday work

- Protecting files and databases at rest

- Securing network connections and APIs

- Password managers and secret sharing tools

- Backups and device storage encryption

If you handle credentials, recovery codes, access tokens, or client data, there is a good chance AES is already working behind the scenes.

The human side of encryption, why breaches still happen

Breaches rarely happen because someone mathematically broke AES-256. They happen because of practical issues like:

- Secrets are pasted into chat or email and stay searchable forever.

- Passwords are weak, reused, or shared too broadly.

- Links to sensitive content never expire and circulate beyond intended recipients.

- Keys or passphrases are stored where admins or vendors can read them.

Good tools and habits reduce the chance of these human-scale failures.

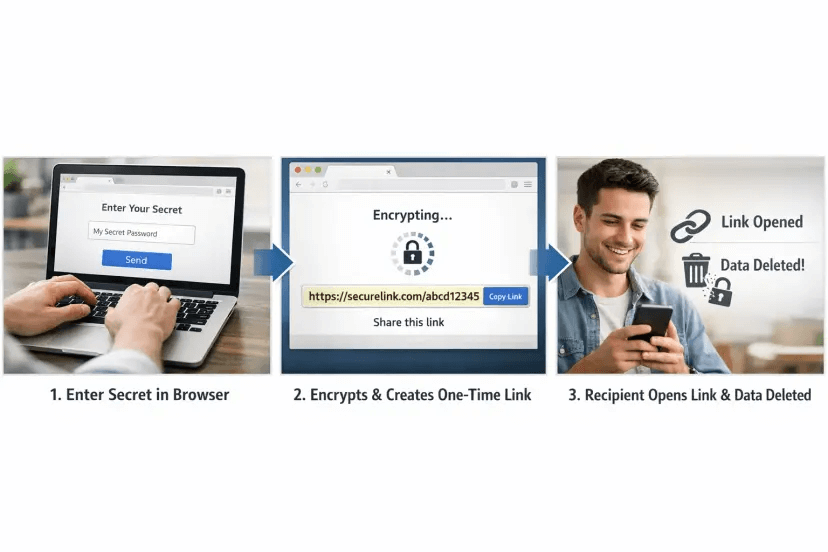

How AES-256 fits into a safer sharing workflow

When you need to share something sensitive, the safest pattern is to separate the message from the secret. Discuss logistics in your normal channel, but transmit the secret through a one-time, encrypted link that destroys itself after it is read. That way, your chat or email history holds only a dead link, not the secret itself.

This is exactly the problem space Nurbak focuses on. With Nurbak, secrets are encrypted on your device with AES-256, never stored or logged by the service, and delivered as one-time, self-destructing links. This zero-knowledge approach means the provider cannot read the secret, because it never receives the decryption key. Learn more at Nurbak.

What actually makes AES-256 deployments secure

If you ask a security team what to watch for in an AES-based system, you will hear the same few themes. Here they are in human terms:

- Client-side encryption, the secret is encrypted before it leaves your device. Providers that cannot see your data reduce insider and legal access risks.

- Authenticated encryption, the system should not only hide the content, it should detect tampering.

- Unique IVs or nonces, think of these as fresh random ingredients that prevent patterns. Reuse is a real risk.

- Strong key derivation, if a passphrase is involved, use a proper key derivation function rather than turning the passphrase directly into a key. This slows down guessing attempts.

- Ephemeral access, one-time links and expirations limit how long a secret can be stolen or misused.

- Minimal data retention, avoid services that keep copies, logs, or keys.

NIST guidance for modes and key management is public and accessible if you want to go deeper, see NIST SP 800-38A and NIST SP 800-57 Part 1.

Common myths, debunked

- AES-256 is overkill, it is true that AES-128 is already very strong for many use cases, but AES-256 provides a bigger safety margin and is often chosen for long term confidentiality policies.

- Encryption alone solves everything, encryption protects confidentiality, but you still need authentication, access control, secure deletion, and good processes.

- A vendor that uses AES-256 is automatically zero-knowledge, AES-256 is a cipher. Zero-knowledge describes architecture. A service can use AES-256 and still retain the keys server side. If you want privacy from the provider, look for client-side encryption.

- Quantum computers will break AES next year, current analysis suggests that while some cryptosystems are vulnerable to large scale quantum computers, brute forcing AES-256 remains out of reach for the foreseeable future. NIST's current recommendations still include AES.

A buyer's checklist for AES-based tools

When evaluating tools that mention aes 256 encryption on the homepage, ask for clear answers to these questions:

- Where does encryption occur, on the client or on the server?

- How are keys created, stored, and destroyed?

- Does the system use authenticated encryption to detect tampering?

- What is the default data retention policy, are secrets or logs kept at all?

- Are there one-time links, expirations, and audit access logs for traceability?

- How does the design support compliance obligations you already have?

If the vendor cannot answer without jargon or hedging, that is a signal.

How Nurbak applies AES-256 for practical privacy

Nurbak is designed for teams that need to share sensitive information without leaving a trace. Here is how it maps to the principles above, without getting lost in acronyms:

- Secrets are encrypted locally in your browser with AES-256 before anything leaves your device, this supports Nurbak's zero-knowledge architecture.

- Links are one time by default, once the recipient reads the secret, the encrypted payload is permanently deleted so your chat or email only contains a dead link.

- No data is logged or stored, this reduces the risk of accidental retention.

- Admins can review audit access logs and analytics for governance without seeing secret content.

- The platform is built to support teams in regulated industries and to integrate with existing infrastructure.

If you are currently pasting passwords into Slack or sending recovery codes over email, switching to a self-destructing, client-side encrypted link removes a long lived risk from your environment. For a practical primer on why this matters, read our guide on why Slack and Microsoft Teams are not safe for passwords.

Quick actions non-engineers can take today

- Stop pasting secrets into persistent channels like chat and email. Share a one-time encrypted link instead.

- Use strong passphrases and a password manager so humans are not the weak link.

- Set expirations on any sensitive link you share. Short lifetimes are better.

- Confirm your vendor's encryption is client side and zero knowledge if privacy from the provider matters.

These habits, combined with AES-256 under the hood, dramatically reduce the chance your organization leaves sensitive information where it can be found later.

Bottom line

AES-256 is the most widely trusted standard for encrypting data today. It is strong, fast, and backed by decades of public scrutiny. But real world security is more than math. The biggest wins come from how you apply AES, for example encrypting on the client, adding authentication, limiting lifetime, and avoiding storage and logs.

If you need an easy way to put these principles into practice, try sharing your next secret with a one-time, self-destructing link at Nurbak. You get the privacy benefits of AES-256 and a zero-knowledge design, without the complexity.